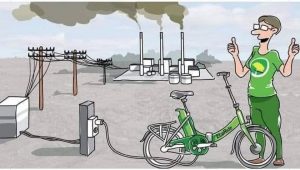

With the rise of electric vehicles, we still have a somewhat obscure dilemma.

With the passing of the decades, humans must consider ourselves, in fact that is already under debate, to be more green, sustainable, etc … The important thing is that we have several alternatives, now, the important thing is to know which of them is the most correct and the origin of everything, how it is born and who gives it as energy to the world of consumption.

some data..

In 2012, in countries such as the United Kingdom, electricity generation from coal increased by 40%, due to the increase in the prices of gas also used to generate energy.

Electricity from coal, which is the most polluting way to produce energy, drastically reduces the advantages of electric cars. For example, as China generates almost all its energy with coal, the analysis of electric cars in the Asian giant showed that they were much more polluting than gasoline cars.

However, in countries like Norway, where much of the energy is produced by hydroelectric plants, electric cars had less environmental impact than normal ones.

“For the average electricity generation in Europe, if you use a car for 150,000 km you can expect an improvement of 25% (in global impact) compared to a vehicle with gasoline”

These results add another dilemma to all those consumers who evaluate whether or not to switch to electric cars.

Aside from questions about your driving or whether you will be able to reach your destination without having to change the battery, the environmental benefits are not always entirely clear.

Now, the rise of Lithium as batteries in vehicles recycling these batteries “is not harmless” to the planet, recycling costs a lot, less only 50 ‘60% can only be recycled and again to disassemble Lithium batteries It requires many highly polluting agents that, to top it all, generate a lot of Co2.

As a planetary organization we see with a lot of “eye” the supposed green energy that we want to sell, in any case we should go slowly and see how it goes to dictate its impact on the environment, its origin and its reuse, in order to minimize the impact and thus help humans to generate their development.